Notes from: McCloud, Scott. (1993).

Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art. New York: HarperCollins Publishers. p. 138-215.

- "Traditional thinking has long held that truly great works of art and literature are only possible when the two are kept at arms length. Words and pictures together are considered, at best, a diversion for the masses, at worst a product of crass commercialism." (p. 140)

- Show and tell: a capable artist uses a balanced combination of pictures and words - balance does not necessarily mean equal amounts, but more that one always complements the other (p. 155)

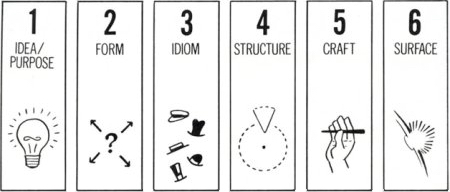

- All artwork follows six steps (p. 170-1):

- Idea/purpose: "the impulses, the ideas, the emotions, the philosophies, the purposes of the work...the work's content."

- Form: book, furniture, music, etc.

- Idiom: "the 'school' of art, the vocabular of styles or gestures or subject matter, the genre that the work belongs to...maybe a genre of its own."

- Structure: "putting it all together, what to include, what to leave out... how to arrange, how to compose the work."

- Craft: "constructing the work, applying skills, practical knowledge, invention, problem-solving, getting the job done."

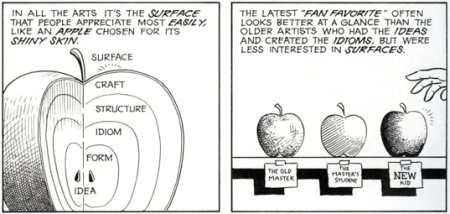

- Surface: "production values, finishing... the aspects most apparent on the first superficial exposure to the work."

- After an artist learns to draw, learns how to craft their drawings effectively, learns the proper structure of making an excellent strip (pacing, drama, humor, suspense, etc), and then learns how to instill in the strip their own identity (idiom), it's then that they can decide to become a "explorer" (p. 179) or a "storyteller" (p. 180) - that is to say, either their strip is about art itself, and they experiment with new ways to convey information/stories, or they have a regular/controlled medium and hone their skills at delivering a message as effectively as possible (p. 173 - 180)

- Color introduction boosted comic sales, but increased cost was also an issue (p. 187)

- Bright, primary colors were used to counteract the dulling effect of the newsprint, so comics were full of primary colors, without any one dominating the other; this eliminated the emotional impact that could could have had (p. 188)

- Colors were also consistent with a given character, and thus became a symbol (p. 188)

- Colors also objectify subjects, bringing attention to the physical form and not just black and white lines (p. 189)

- When hue and shading starting being introduced in the 1970's, it didn't match the line drawings of the action comics - they fit better with the original 4-color scheme; thus, the surface changed without the core changing (p. 191)

- While color may bring more reality to a comic strip, that may not be what a reader wants - black and white comic strips will always have a home (p. 192)

- So, why are comics so important? No human can ever truly know what it's like to be in the mind of another (p. 194), and the only way to at least try is to communicate. There are many ways to communicate, but it's essential that we understand the different forms that can take (p. 198)

- "Creator and reader are partners in the invisible, creating something out of nothing, time and time again." (p. 205)